If you’d like to be a guest columnist, please click here.

There is one incident in my life that I have always remembered and told and retold to audiences that had an interest. It occurred during summer break between my second and third years of Law School. 1958.

I had either turned 23 or it was nearly my birthday. And my wife, June and I, along with our first child, Karen Madeline, were living at the Harris Homestead, on Enon Ridge, here in Birmingham. My mother, Madeline Harris Davis, and her sister, my aunt, and uncle who also lived there, were all registered voters.

That was highly unusual for Negroes in Birmingham, Alabama in 1958. I don’t know the exact number of Negroes registered to vote in Birmingham in 1958 but four years later, in 1963 at the time of the change in the form of government of Birmingham, I believe the total Negro voting population was 4,000.

My mother casually asked if I was a voter. The question hit me squarely between the eyes since I was a graduate of Talladega College and a student at the State University of New York in Buffalo School of Law.

I knew of the struggle of Negroes, as we were then called, to become registered voters in the South. Or for that matter, all over the United States in the period before the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Negroes made up a substantial part of the population of the state of Alabama and a large Negro vote would have a decisive effect on the outcome of an election between an arch conservative and a more moderate candidate.

The Republican Party was of minuscule size in Alabama because of its identification with the Negro vote during the Reconstruction Period that had ended only eighty-two years in the past. This identification was distasteful to whites and caused them to shy away from Republicanism, as it is today with their distaste for the Democratic Party.

The rise in Republican numbers did not begin in Alabama until 1964 with the Goldwater candidacy for President against Lyndon Baines Johnson. That election caused large numbers of arch conservative white voters to switch from the Democratic Party to the Republican Party. The increase in whites becoming members of the Republican Party was headed by a Birmingham lawyer, John Grenier, who led the effort to increase the Republican Party by vast numbers. Negros who had voted Republican since obtaining the legal right to vote, after the end of slavery, switched to the Democratic Party with the election in 1932, of Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

Back to the story. Momma’s question was asked during breakfast, and I then dressed in a shirt, tie, and a suit and went down to the Jefferson County Courthouse to become a voter. During that time, it was common for a Negro to dress well for it was thought that whites treated Negros better who were well dressed. That may have been true in some instances, but generally not.

I found the location of the office of the Board of Registrars and went in. I asked to become a registered voter. The Board was then composed of three whites in every county in the State of Alabama, one of whom was generally a female. Upon asking the lady at the counter to give me a Voter Registration Application, she complied, and did so, and she instructed me to go have a seat and fill out the questionnaire.

I quickly completed the application and turned it in to the lady. The process, at that point, was to comply with the statutory requirements of showing literacy. This was done generally only to Negros. This was the way that the Board of Registrars could show that, in their estimation, blacks were not literate enough to be good citizens, and therefore, not voters. If I was able to write down the answers to the questions, that must have been read, that action would have shown, in and of itself, literacy. Being able to read and write. It’s literal meaning.

I could see from the lady’s facial expression that she was surprised at my quick ability to show competence. She then told me she would ask me questions that she wanted me to answer. The lady then asked me to explain the Fourteenth Amendment of the United States Constitution.

I had just taken the course in Constitutional Law that immediate past semester. The Dean of the Law School, Jack Hyman, was a very thorough professor and he taught the course. He knew that I planned to return to Birmingham to practice law and told me that I had to know Constitutional Law almost verbatim in order to practice in Alabama because he knew that this was the beginning of the Civil Rights era. I then recited all I knew about the Fourteenth Amendment, all of which was head and shoulders above the knowledge of the lady questioner. Her facial expression was that of utter surprise that I had such legal knowledge.

Being flabbergasted at the end of my recitation, she asked me how I knew so much. To which I replied, that if she had read my application, she would have seen that I was a rising third year student at the Law School of the State of New York. She then put her hands in the air and looked at me sideways and said, “If you know so much, tell me if there is a woman elected to the Senate of the United States.” I knew the answer immediately because during that time, at our home, there were LIFE Magazines and LOOK Magazines that were subscribed to. These magazines were full of stories about women who were progressing in politics. To answer her question, I said “yes, yes ma’am, her name is Mrs. Margaret Chase Smith, a Republican from Maine.” At that time, the lady raised her hands in disgust, and slammed them on the counter and uttered, “Oh Hell, just let the Nig… vote.”

I left the Board of Registrars with my Certificate of Registration in hand. All of the foregoing calls for other stories of Racial, Jim Crowe, segregation, that were caused by my leaving the state of Alabama to go to an out-of-state Law School at the expense of the state of Alabama. If so, requested by the editor, I will write about them at a subsequent time.

(Editor’s note: (This year marks the 150th anniversary of the ratification of the 15th Amendment on February 3, 1870. The 15th Amendment asserted that neither the federal government nor state governments could deny voting rights to any male citizen.)

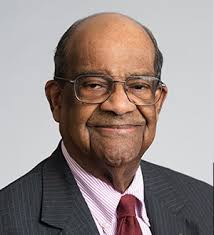

J. Mason Davis has been practicing law for 60 years, 36 of which he has been a senior partner at Sirote. He celebrates his 85th birthday this week. He has a long, distinguished career representing clients in business, antitrust, securities, and product liability litigation, as well as life, health, and surety company defense. His appellate practice includes matters before the Supreme Court of Alabama and the Fifth and Eleventh Circuit Courts of Appeals.

Click here to sign up for our newsletter. (Opt out at any time)

David Sher is Co-Founder of AmSher Compassionate Collections. He’s past Chairman of the Birmingham Regional Chamber of Commerce (BBA), Operation New Birmingham (REV Birmingham), and the City Action Partnership (CAP).

Invite David to speak for free to your group about how we can have a more prosperous metro Birmingham. dsher@amsher.com.

A very good story and remembrance of the awful “troubles.” Was there a reason why Attorney Davis used the Jim Crow term “Negro” instead of the more acceptable term “Black” or “African-American?”

Perhaps he chose to use the term because, in the context of the times, it was the term that was considered respectful by Negroes. Dr. King chose both it and “Black” so it must be acceptable in their eyes. In my older adolescent years, “Negro” was being slammed in favor of “Black” by the younger generation as they saw it as a rejection of old norms. I remember many of their parents didn’t like the change and stuck with the old. Same thing happened when another cohort decided “African-American” was better; today I have an older colleague who dislikes it immensely. My advice is to be sensitive to the preference of the people around you, especially if they’re “Black” or “African-American.” “Negro” appears to have become offensive, generally because the people that chose it for themselves have either passed away or are in their 90’s.

This is an excellent piece though I take issue with the idea that the growth of the Republican Party amounted to much in Alabama before the 90’s. I know it didn’t since I worked in party politics from 1983 until I moved to Tennessee in 1991. The voters chose Republicans in presidential races but otherwise we were on a shoestring. I worked for the losing candidate in both US Senate and House races in the late 80’s – believe me, my paycheck was meager. Guy Hunt was an unfortunate accident thanks to the Baxley/Craddick debacle in the Democratic primary. Framing it in racial terms for that timeframe is deeply troubling and offensive.

The mass migration of candidates came later and I lament the fact that so many Dixiecrats like Shadrack, Beeson, and Merrill switched parties. They may have an “R” next to their name but philosophically and ideologically they’re still, in my opinion, old-line Democrats.

Then again, most of us from the old days are labelled as RINO’s.

He was simply referring to the term used “back then.”

J Mason Davis drove down to Tuscaloosa once a week to teach a law school class when I was there. He was an excellent teacher and a scholar and a gentleman. He has given back so much to our community and we all owe him a debt of gratitude.

Wonderful article and gave me a better understanding of the difficulty facing black voters in Alabama. What an inspiring story of success and determination

Mr. Davis is a living treasure. Please, can we hear more from him?

Mr. Davis, this is priceless. I am in awe of Blacks in our generation (I’m white but we’re close to the same age!) who navigated shark-infested waters every day and have somehow maintained their dignity, grace, hope, and determination through their lives.

Thank you for staying to help make this a better community. And shame on a White person who can look at ANY black person and assume “I’m most certainly smarter than him or her.” Astonishing.

He mentioned that he was just using the “term” that was common at that time: “I knew of the struggle of Negroes, as we were then called…”

The best raconteurs live in Alabama. This piece might need to be in the national press! Keep this good stuff coming, David. Dan

Mr. Davis, Thank you for this wonderful story. We must never forget history and you are living history!

Would love to see more articles from Mr. Davis.

Eileen Lewis